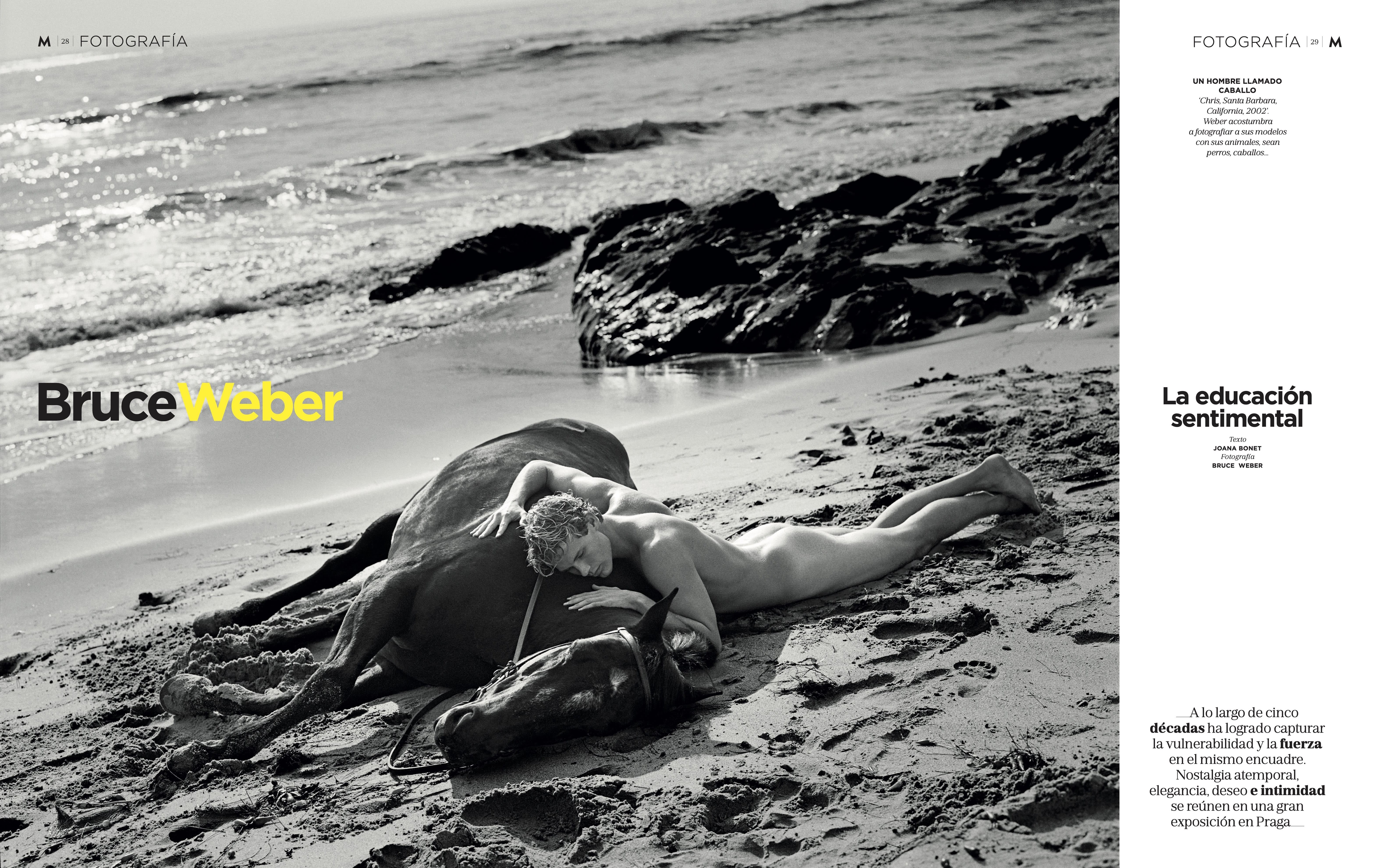

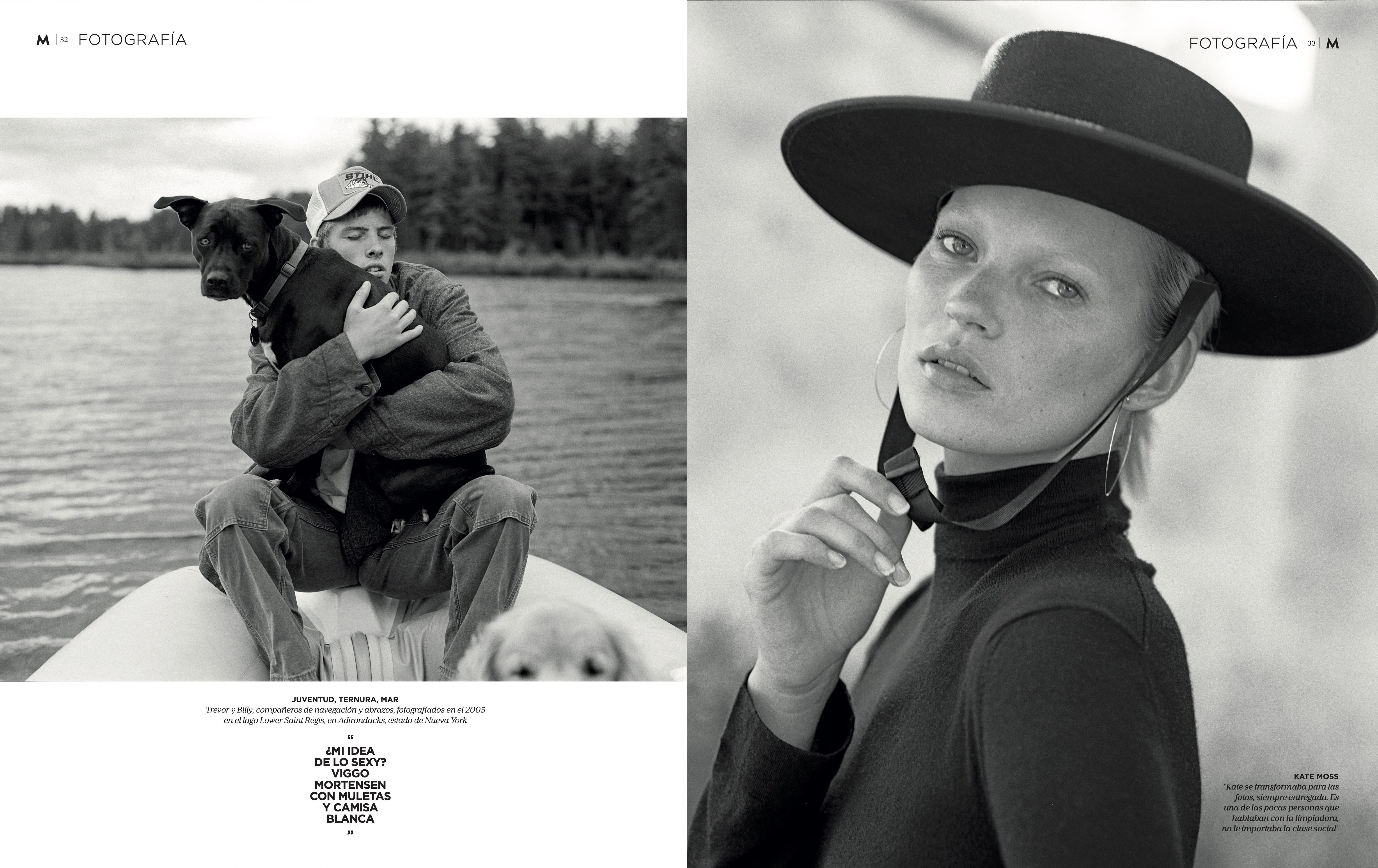

Over five decades, he has managed to capture vulnerability and strength in the same frame. Timeless nostalgia, elegance, desire, and intimacy come together in a major exhibition in Prague.

My parents had a beautiful garden in Pennsylvania. Our backyard overlooked a farm with many animals. During the summers, life revolved around the garden, where my father filmed movies and took photographs. My uncle and my grandmother also took photos… everyone was taking pictures. On Sunday nights, we went to watercolor classes. At that time, I didn’t consider all of that an education. I was young and focused on other things. But as I grew older, I realized that this education was the foundation upon which I built my perspective, my way of seeing and telling things.” The speaker is Bruce Weber via Zoom from the home he shares with his wife, the great collector and producer Nan Bush, in Montauk (New York). It is eleven in the morning, and one of his white golden retrievers comes in to greet him. Behind the table are long shelves displaying part of his photography collection, from Cartier-Bresson to Irving Penn. None of them are his. “I don’t have them hanging at home because I live with them almost 23 hours a day,” he says.

You are a photography collector ...

Yes, and I mix them all together. I have both works by contemporary photographers and pieces I found at flea markets that I love. I am impressed by those people's ease, their body language, the way they shake your hand... Not much is written anymore about how people shake hands, and I find it interesting because it's your first introduction to someone. If they grip your hand too hard, as if trying to break it, it's uncomfortable; on the other hand, if they offer it in a pleasant and sincere way, it's a beautiful gesture.

Do you think a lot about the composition of the image before shooting?

No, it just happens. I still cross my fingers and pray if I'm nervous before taking a photo. But when I'm walking down the street with my camera, I just hope to get lucky. And I've had a lot of luck in my life. I've always had good people around me. My wife, my sister, who worked in the music industry and collaborated with David Bowie and Frank Zappa... I've also had good friends who had nothing to do with photography. My college roommate, for example; the most handsome guy in college. He built his own motorcycle with spare parts. And it turned out beautiful! He brought it to college in Ohio. By the way, I went to a Baptist university as a Jew, which is a bit crazy... He would take me for motorcycle rides in the afternoons after class, and I would take pictures of him, the motorcycle, the landscape. And I thought, “Wow, this photography thing is so much fun!” I also had photographer friends, and we started out together. We were very poor and admired the great authors from Paris or New York, who dressed very well. I would tell them: “It’s not so important how we dress, but how we feel about our work.” Because there were also greats like Irving Penn, whom I admired, who always wore the same wrinkled denim shirt with a pair of pants and a simple sweater. Nothing more.

Was Diane Arbus the one who pushed you to pursue photography professionally?

Dick [Richard] Avedon recommended that I study with Lisette Model, a great European photographer who lived and taught in the countryside. I had to go meet her in person and show her my photos before being admitted to her class. I never thought she would accept me. I think she liked me because I was a bit crazy. Every night after class, we would go to a very typical restaurant in the United States, Howard Johnson’s, and I would sit with her at the counter. We ate hot dogs, drank Coca-Cola, and talked about art, photography, love, terrible people, good people, all sorts of things related to photography. One night Lisette told me, “I hope you meet Diane Arbus someday.” And by chance, I did. Once again, I was very lucky: I was visiting my parents in Florida with barely a dollar in my pocket, enough for a tea or coffee, nothing more. I saw her and approached her, saying, “Hi, my name is Bruce Weber, and I’m going to study photography with your teacher. I just wanted to tell you how much I love your photos.” She asked me, “Are you rich?” —I don’t know why she thought I was— and I replied no, that in fact I was very poor. “Do you want to take pictures like mine?” she asked me. I told her that would be impossible because I couldn’t be her; and she responded, “That’s fine… sit down.” We became very good friends because we had a lot in common. She would call me at four in the morning to tell me she was going to throw away her photos, and I would try to convince her not to; “They’re too valuable,” I would say...

She was looking for strange creatures. In contrast, you have portrayed the United States from a place of optimism. Is your work the idealized American dream?

I think in our photographs, we seek out people we would want to be friends with. And I believe that is one of the reasons why, in the end, Diane couldn’t take it anymore. Everyone she photographed wanted to be her friend, from the giant Jewish man to the little boy with AIDS. They called her constantly… When you photograph someone, whether you like it or not, that person will be with you forever.

Do you still find fashion enjoyable?

Definitely not. Most of the fashion brands I worked with were family-owned companies, whereas now, with large corporations, everything has become about money. Something essential has also been lost: today they hire young people—which is good because it gives them an opportunity—but then they don’t provide the necessary support. In contrast, when I was young, I worked with many great fashion editors who would become like brothers or sisters to me. We didn’t just talk during work; we were friends. And we learned from each other. The situation is different today: there are few opportunities and no artistic freedom.

And if a publisher gave you complete freedom, would you return?

Actually, no. But if someone close to me, or even someone I just met, asks me to create something beautiful, then I would be willing to do it.

Noted. How do you manage to work almost simultaneously with Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren, two major icons of American fashion?

I was with them from the beginning, and back then they weren’t as big. With Ralph, I started by doing a portrait of him for *Harper’s Bazaar* with his family. His children were small. And in Calvin's case, we had many mutual friends. One day he called me to his office and said, “I’m thinking of you to photograph my new jeans campaign. I have a boyfriend named Romeo, and I want him to be in it.” I started laughing because it seemed strange and wonderful to have a boyfriend named Romeo. I asked him, “What’s he like?” That guy looked a lot like James Dean. Back then, people in fashion felt such passion for what they did that they were willing to live and die for their work. The fashion world is no longer like that. I always felt that photography wasn’t a matter of life or death but a means to learn, to grow, and to reach something. And I never appreciated only my own photographs but also those of many of my colleagues...

Do you maintain a good relationship with Ralph Lauren?

Ralph is quite a character. Always changing clothes... Back then, everyone who worked for him would arrive at the office dressed for horseback riding. And he has a great collection of cars. He’s the kind of person who is never satisfied or happy. I think that’s one of his great virtues because he always wants to improve. The first time I went to his ranch, I met his children, his wife, and him... I respected and admired him a lot. He told me, “We want to give an image as if Jessica Lange and Sam Shepard were in the photos,” and I replied that I wasn’t a plastic surgeon, but a photographer. I used to say things like that to him because he lives in a bubble. I never treated the people I worked with condescendingly; I always had a lot of respect for them. But I wouldn’t let anyone trample on me.

What were your early years like?

When I started, the older ones were very kind to me. Most of my closest friends, when I was 20, were between 80 and 90 years old. Mary Ellen Mark, a wonderful photographer, asked me if any art director had ever told me they liked my photos, to which I replied no, never. She then told me that people always talked about colleagues who had photographed the person in front of her lens, only to add that there were better photos than theirs... She was very depressed at that moment. And Helmut Newton, who was present in the conversation, asked me why I was wearing jewelry and told her that he didn’t like her photos either. Mary Ellen started to cry. We need to treat each other with empathy because this profession is very tough.

Who has been the best fashion editor for you?

Ingrid Sischy, who ran *Interview*. She was an intellectual, almost philosophical, and at the same time very funny. Working together felt like going back to high school newspaper days. There was a lot of freedom in America back then.

Do you like the current world?

Yes, of course. It’s true that, on one hand, it saddens me to see how tumultuous the world is. But I have always sought something to photograph in life, something I wanted to know for myself. And that has made me feel the happiness of being alive. It’s that simple! I’m more optimistic than apocalyptic.

What attracts you so much to vulnerability? Was that the reason for your strong connection with Chet Baker?

His music was wonderful, and I wanted to protect him. You don’t really know someone until you work with them on a film and you’re immersed in it together. It was very difficult but also a lot of fun. He resembled my mother a lot. My parents loved each other deeply: there was a strong attraction between them. However, they drank too much and argued all the time, although they never separated. I never understood why. Later, I realized there was no one else in the world they wanted to be with. I think that’s why my father took such beautiful photos of her. Sometimes in a bathrobe, other times in a lovely dress… I still keep them. I have always felt close to people who have gone through catastrophes.

How would you define sexy?

I met Viggo Mortensen when he was still a model and an amateur photographer dreaming of becoming an actor. He didn’t have much work, and I offered him to come with me to shoot Chet. “You can be an extra in a group of handsome young guys I want to film in Santa Monica playing pool,” I suggested. One day we hired him for a job with Chanel, and he showed up on set with a broken foot and crutches, wearing a white shirt and jeans. I remember thinking, “What a handsome guy, so willing to work, so sexy.” I don’t know if that counts as a definition.

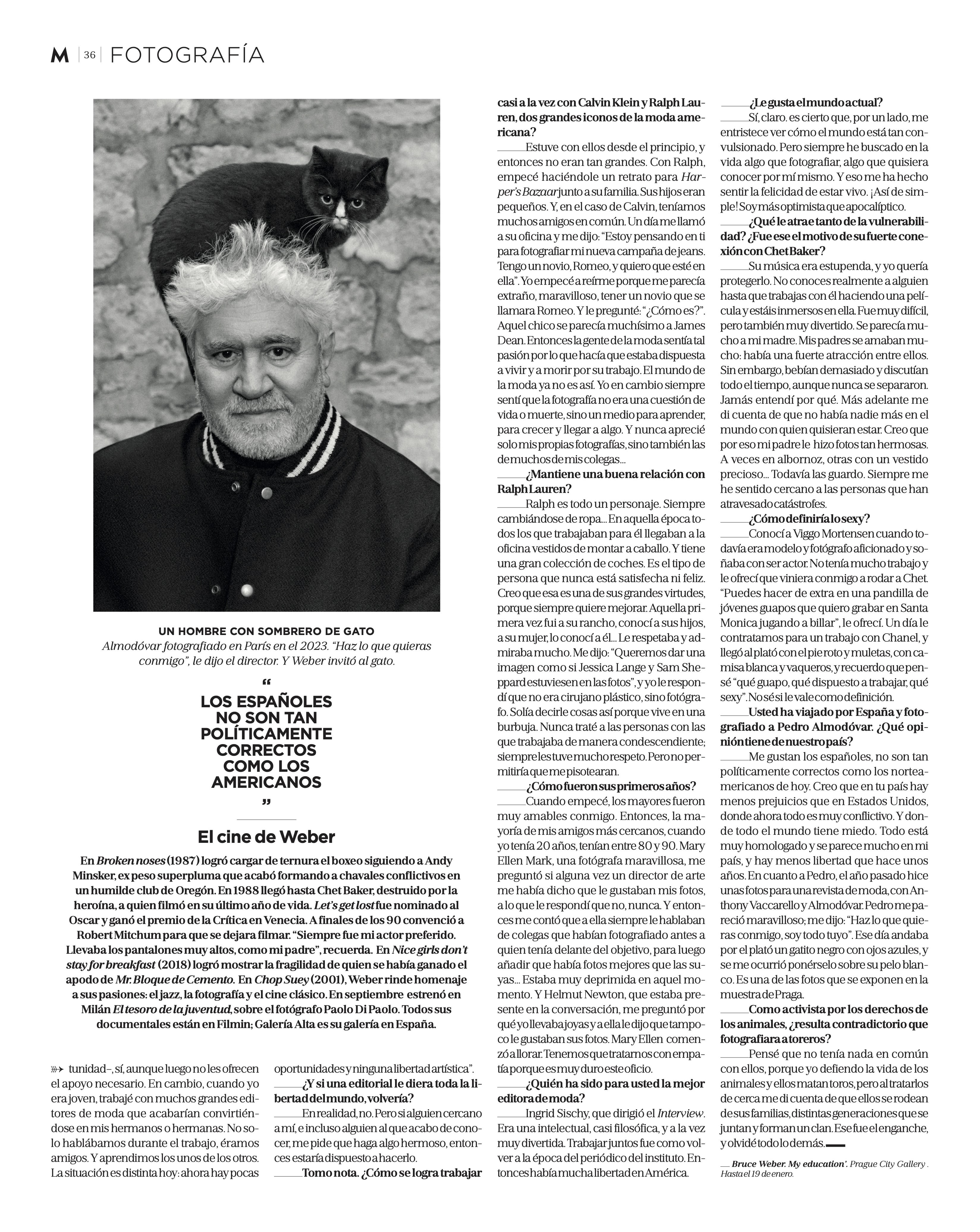

You have traveled through Spain and photographed Pedro Almodóvar. What do you think of our country?

I like Spaniards; they aren’t as politically correct as Americans today. I think there are fewer prejudices in your country than in the United States, where everything is very contentious now. And where everyone is afraid. Everything is very standardized and resembles my country, and there is less freedom than there was a few years ago. As for Pedro, last year I took some photos for a fashion magazine with Anthony Vaccarello and Almodóvar. Pedro seemed wonderful to me; he said, “Do whatever you want with me, I’m all yours.” That day there was a little black kitten with blue eyes wandering around the set, and I thought to put it on his white hair. It’s one of the photos exhibited in the show in Prague.

As an animal rights activist, is it contradictory that you photographed bullfighters?

I thought I had nothing in common with them because I advocate for animal life while they kill bulls, but when I got to know them closely, I realized they surround themselves with their families—different generations coming together to form a clan. That was the connection, and I forgot everything else.

Weber's Cinema

In *Broken Noses* (1987), he infused tenderness into boxing by following Andy Minsker, a former super featherweight who ended up coaching troubled youths at a humble club in Oregon. In 1988, he turned his lens on Chet Baker, devastated by heroin, capturing him in his final year of life. *Let’s Get Lost* was nominated for an Oscar and won the Critics' Award at the Venice Film Festival. In the late '90s, he convinced Robert Mitchum to allow himself to be filmed. “He was always my favorite actor. He wore his pants very high, like my father,” he recalls. In *Nice Girls Don’t Stay for Breakfast* (2018), he managed to show the fragility of someone who had earned the nickname Mr. Cement Block. In *Chop Suey* (2001), Weber pays tribute to his passions: jazz, photography, and classic cinema. In September, he premiered *The Treasure of Youth* in Milan, about photographer Paolo Di Paolo. All of his documentaries are available on Filmin; Bruce Weber is represented by Galería Alta.